Note: At the end is a description of the legal system for resolving disputes. Though it is (thankfully!) not accompanied by photos, I think you will find it interesting to read…

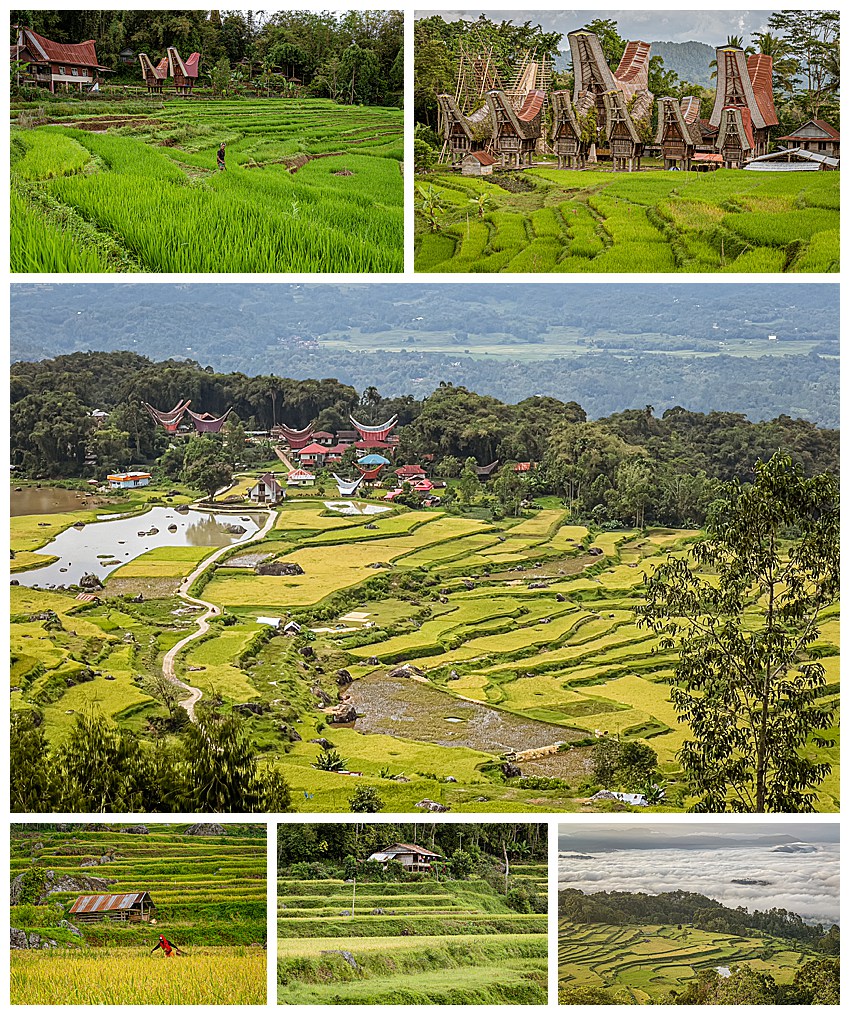

Indonesia is the third largest producer of rice in the world. As we drove through the countryside, we often saw rice terraces sprawl out below us (center). When we saw them, we all screamed STOP! to the driver, so we could clamber out and capture the image. Some rice terraces unfolded below us after photographing a sunrise, as the fog rolled past (lower-right). Still others were found on the sides of the road as we walked past small villages (lower-left and lower-middle).

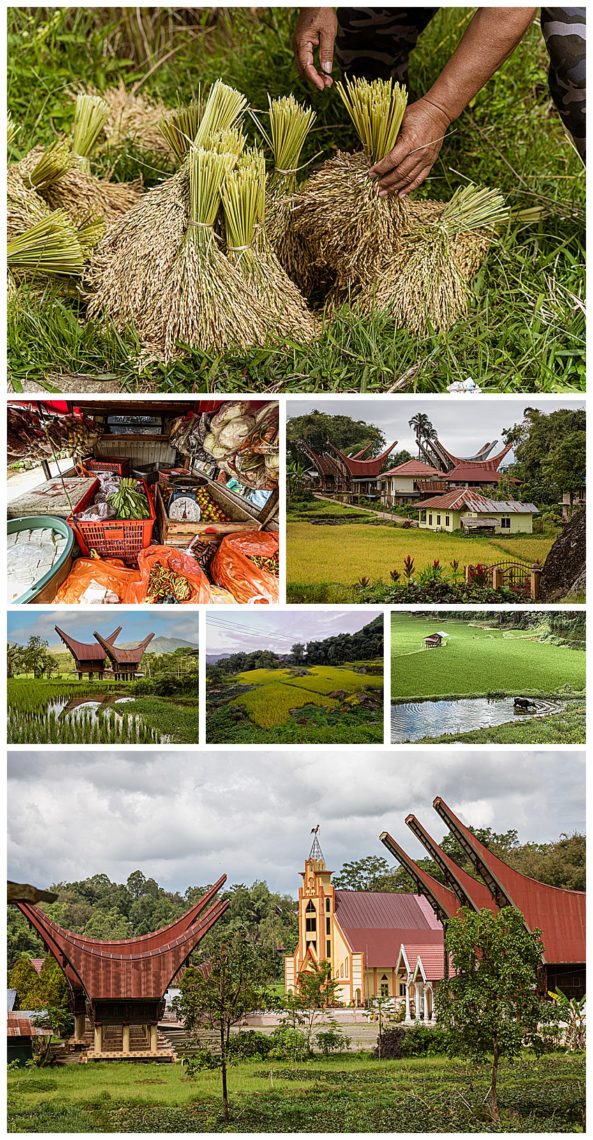

As we noted in an earlier blog post, most prestigious Torajan homes are built with adjacent rice barns. The rice is prepared into small bundles (top) and dried before placing them in the rice barns for future use. If the rice is not properly prepared, the rice will continue to grow inside the barn, and then mold.

Because there is no refrigeration in most villages, each family must shop daily for their daily meals. This has spawned many entrepreneurs who load up their vehicles with vegetables, spices and other daily needs, and then drive to each nearby village to allow the families to buy their foods more easily. These vendors are usually found with heavily loaded motorcycles, though we saw a few with pickup trucks (second row-left).

Despite the Aluk death rituals, the majority of the Torajan population is actually Christian, and it is common to see churches in these villages (bottom). Occasionally, water buffalo can be seen grazing in the fields (third row-right). These buffalo are being raised for a future funeral sacrifice, and are therefore never put to work.

As we drive along the road, we occasionally see workers in the rice field (center). Sometimes we would walk through the rice field areas, and then see the workers up close. Rice fields are planted on a staggered schedule, since the weather is ideal year-round, and this makes it easier to harvest.

Rice is always planted by hand, with small clumps of young rice shoots stuck into the mud under a few inches of water (top row). As the rice grows, it becomes green (middle) and needs only minimal tending. When the rice turns yellow, it is ready to harvest (middle-left and lower-left), which is almost always done by hand in Toraja. Workers are transported to their daily site in the fields by motorcycles, and sometimes by trucks (lower-right).

You can still see the Torajan villages with its defining boat-shaped rooftops at the edge of the rice fields. Some say that the Torajan ancestors arrived by water and slept in their boats, thus the unique architecture is a reminder of their history.

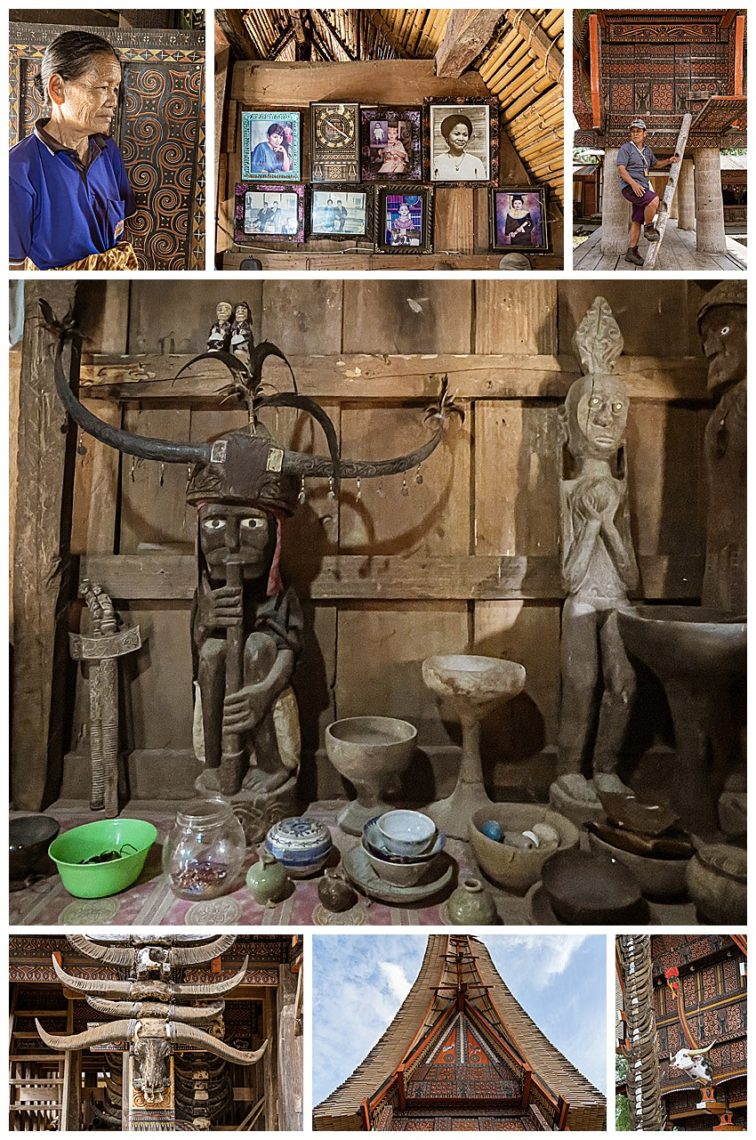

Tongkonan are the traditional Torajan homes, which may only be occupied only by the Upper Class families. Commoners must live in smaller homes. These houses are generally aligned on a north-south axis and the interiors are small and designed only for sleeping and storage. They generally do not have windows. The houses are built without nails, using tongue and groove joinery technique.

The older Torajan homes were made exclusively with bamboo. The newer Torajan homes use modern materials though, such as brick sides and metal for their roofs. Sometimes they even have contemporary first floor living spaces, though they are still built with the saddle-back roofs placed above the modern living structure.

We were invited to visit the interiors of two of the homes. The decorations are simple with some antiques and a few old photos. In the first home we visited, the cooking is done outside the house. The ladder to enter the rice barn is shown by our local guide, Sada (top-right), and was comprised of a simple notched bamboo pole.

Outside decorations are mostly buffalo horns. We were surprised how small and cramped the living quarters were for the wealthy. The Torajans spend their daily lives on the outside of their homes, and use their homes only for sleeping. Even furniture is almost non-existent inside the homes.

We were also invited to the home of Marten Tonapa, a prestigious man who died in March 2022. Funerals for the upper caste in Toraja generally occur during months of the year when it is easy for worldwide family members to attend, typically in July, August and December. It also takes many months to prepare for a funeral of a prestigious member of the village. As such, it is common for the deceased to be kept inside his home for months, or even years — sometimes as long as 20 years, before he receives a proper funeral and burial.

After dying, the person’s body is treated with various tree saps or formaldehyde to prevent decay. He is then placed in a cushioned blanket, and then in a casket. That casket is kept in the home in which the person lived (top). Between the period of the person’s corpse being placed in the home and his final funeral, he is never referred to as being dead. Instead he is referred to as being sick.

The coffin is typically placed in the childrens’ room, and the children then sleep next to the coffin until the burial takes place. Twice daily the family members are expected to place food, water, even cigarettes next to the coffin, so that the “sick person” is never hungry or thirsty, and remove those offerings a few hours later. The coffin is never left alone during this period, and someone must always be in the house so that the deceased is able to get food, drinks, and conversation.

In this instance, the deceased was a wealthy landowner with a large successful upscale restaurant. Despite the wealth, the entire living space of his home, with 3 generations living together, was smaller than the living room in our Honolulu condo.

Torajan homes of prestigious families are typically found in a row, with rice barns directly across from them. They provide an interesting architectural graphic, as seen above.

Following is a description of the Torajan legal system. I can guarantee you would never guess how they handle disputes…

While we were at the first home, Sada, our local guide, told us about the Torajan legal system for resolving land disputes. There are no legal written title records anywhere, and the ownership of land is only a verbal description handed down among the families. Sometimes there becomes a dispute between families over who owns the land though. How is that resolved?

The two families each choose one rooster, and they have a “cock fight.” Whichever family’s rooster wins is the legal owner of the land. (Yep, not kidding!) But what if the losing family does not accept the decision?

Then a champion from each family is chosen, and they each dive into a “fish pond” (10 foot deep holes in the middle of rice fields, to capture the fish in the fields). Whichever champion stays down longest (without dying) wins, and his family now owns the land. (Again, this is true!) But what if they still do not accept the decision?

The final level of the Torajan legal dispute mechanism again calls for each family to choose a champion. Each champion must then thrust his hand into a cauldron of boiling water. It is believed that if you are the true owner, then the gods will protect you, and your hand will come out unharmed. The champion that keeps his hand the longest in the boiling water owns the land.

There is no fourth step. Boiling water is their version of a Supreme Court decision.

We were told that most families accept the result of the cockfight. It seems there are few Champions willing to test the ownership further…